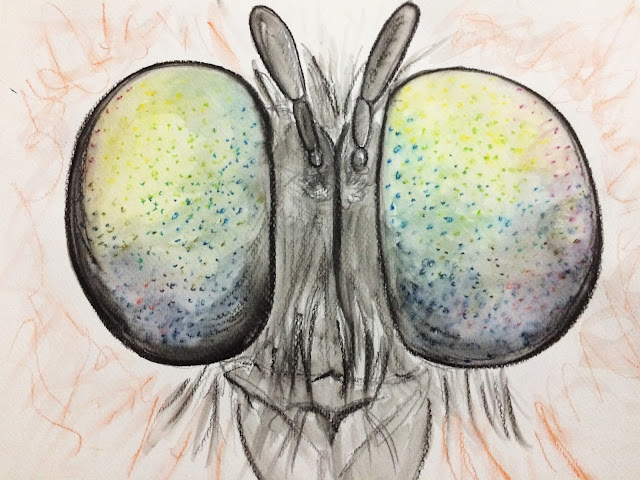

Manchmal frage ich mich, wie die Welt aus der Perspektive einer Fliege aussieht. Durch ihre Facetten-Augen, den Occuli Compositi, haben die Insekten zwar eine eingeschränkte Auflösung, sehen also nicht so klar wie wir, haben aber dafür ein wesentlich größeres Blickfeld und können auch Bewegungen viel schneller wahrnehmen. Ich könnte also vielleicht sogar die einzelnen Flügelschläge eines Kolibris erkennen.

In vielen Sprachen gibt es das Sprichwort, dass man "durch

viele Augen besser sieht", also durch verschiedene Perspektiven in seinem Urteil

bereichert wird. Dies möchte natürlich nicht sagen, dass die Anzahl der Augen

der entscheidende Faktor ist, sondern die Kombination verschiedener Augen mit

verschiedenen, denkbefähigten Wesen. Und woher kommt dieses Sprichwort? Können

wir unseren eigenen Augen etwa nicht trauen?

Was sehen wir wirklich durch unsere Augen? Sie bilden

das ab, was wir oft als die Realität akzeptieren. Und sicher ist das, was unser

Sehorgan isoliert produziert, ein recht zuverlässiges Abbild, eine Art Foto der

Realität. Was passiert aber danach? Der Sehprozess ist schließlich etwas, bei

dem wir nicht strikt zwischen Bildaufnahme und Bildverarbeitung unterscheiden

können, wie es bei manuellen Kameras möglich war. Die Verarbeitung der neutralen

Bildinformation durch unser Gehirn ist ein direkt angeschlossener, untrennbarer

Prozess.

Was sehen wir wirklich durch unsere Augen? Sie bilden

das ab, was wir oft als die Realität akzeptieren. Und sicher ist das, was unser

Sehorgan isoliert produziert, ein recht zuverlässiges Abbild, eine Art Foto der

Realität. Was passiert aber danach? Der Sehprozess ist schließlich etwas, bei

dem wir nicht strikt zwischen Bildaufnahme und Bildverarbeitung unterscheiden

können, wie es bei manuellen Kameras möglich war. Die Verarbeitung der neutralen

Bildinformation durch unser Gehirn ist ein direkt angeschlossener, untrennbarer

Prozess.

Und was passiert während der Verarbeitung? Ein erster signifikanter

Verarbeitungsschritt ist die Filterung der Information. Damit wir nicht völlig von

der Flut an Sinnes- und Bildreizen überfordert werden, grenzt unsere

Wahrnehmung (unser Thalamus) also zunächst viele Informationen aus, die nicht im Fokus unserer

Aufmerksamkeit stehen und nicht bedrohlich erscheinen. Die Informationen, die

uns erreichen werden beeinflusst von Emotionen und Erfahrungen, wie einige (evolutions-)

psychologische Experimente gezeigt haben (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3203022/, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4141522/).

Es sind noch immer nicht alle Prozesse abschließend geklärt und erforscht,

trotzdem wird deutlich, dass uns nicht alles erreicht, was als Lichtwelle in

unsere Augen fällt und das, was uns erreicht auf dem Weg modelliert wird.

Sollten wir uns also vielleicht öfters fragen, was

wir grade wirklich sehen? Und was in uns, welche Emotion, welche

Erfahrung, das Bild, das wir grade empfangen, vielleicht positiv oder

negativ einfärbt und verändert?

Sollten wir uns also vielleicht öfters fragen, was

wir grade wirklich sehen? Und was in uns, welche Emotion, welche

Erfahrung, das Bild, das wir grade empfangen, vielleicht positiv oder

negativ einfärbt und verändert? Sometimes I ask myself what it would be like to see the world from the perspective of a fly. Through its facet eyes, the occuli compositi, the insects have a limited visual resolution, so their images are bit more blurred than ours, but therefore their field of vision is much vaster as well as their perception for movement. I could maybe even see the wings of the flying Colibri.

In many

languages we have the saying that “through many eyes you can see better”, that

our judgement is better through more perspectives. Of course, this saying does

not want to imply, that the number of eyes is the important variable but the

combination of many eyes and many thinking minds. And where does this saying

come from? Is it, that we cannot trust our own eyes?

What do we

really see through our eyes? They seem to project, what we often accept as our

reality. And for sure our visual organ by itself is capable of producing a

pretty precise image of the real world, almost a photograph of the reality. But

what happens afterwards? The process of “seeing” is, finally, a process in

which we involve not only our visual organ but also our brain, we cannot separate

the process of “taking the picture” and processing it, as old, manual cameras

are able to do. The processing through our brain of the raw image we captured

is inevitably linked.

And what

happens while processing? A first, very significant event is filtering the

information. For us to not completely be lost in the vast amount of visual and

other sensational information reaching our brain, our conscious (our thalamus)

sorts out a great amount of the input which happening outside our attentional

focus and which does not appear to be harmful. This information, which really

gets through to our conscious is then influenced by emotions and personal

experiences as some (evolutionary-) psychological experiments demonstrated (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3203022/, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4141522/). Still,

many mysteries remain unexplained, but I think the main idea is clear: we do

not perceive all information which is transmitted into our eyes through light

rays and what really gets to us is modified along the way.

So, should

we, maybe, question ourselves more about what we really see? And what inside

us, which emotion, which experience, is changing our perception, altering the

image in a positive or negative way?

Algunas

veces a mí me pregunto parezca el mundo de la perspectiva de una mosca. Con sus

ojos de facetas, los occuli compositi, los insectos tienen una resolución

visual peor que la de nosotros, pues, vean más borrado que nosotros, pero

tienen una vista mucho más amplia y además perciben movimiento mucho mejor. Yo

podría, tal vez, incluso ver las alas de un colibrí, entonces.

En muchos

idiomas existe, en una forma u otra, el dicho que con “más ojos se vea mejor”,

que su juzgamiento se mejore con más perspectivas. Y, por supuesto, el dicho no

implica, que el hecho importante sea el número de los ojos, pero la combinación

entre el número de los ojos y los individuos a quienes pertenecen los ojos que

piensen. ¿Pero de dónde viene ese dicho? ¿Implica que, al fin, no podemos

confiar en nuestros propios ojos?

¿Qué

realmente vemos a través de nuestros ojos? Presentan a nosotros, que

normalmente llamamos y aceptamos como nuestra realidad. Y es cierto, que

nuestro órgano visual a su mismo crea una imagen muy adecuada de nuestro

entorno, casi una fotografía de la realidad. ¿Pero qué pasa después? El proceso

visual, al fin, no solamente involucra nuestros ojos, pero también nuestro

cerebro, no podemos separar el proceso de hacer y procesar la imagen como las

cameras manuales pueden. El procesamiento de la imagen neutral a través de

nuestro cerebro es un proceso que sigue directamente y no se puede separar.

¿Y qué pasa

mientras estamos procesando? Uno de los primeros pasos es que nuestro cerebro

está filtrando la información que percibimos. Para que no totalmente nos

perdimos en la inmensa cantidad de visual y sensacional información que llegue

a nuestro cerebro, nuestra “consciencia” (nuestro tálamo) tiene que filtrar una

gran parte del “input” que pasa fuera de nuestra atención y no implica ningún

peligro para nosotros. Esta información, que realmente llega a nuestra

consciencia está, cuando entró, influida de emociones y experiencias propias

como demuestran algunos estudios psicológicas-evolucionarias (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3203022/, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4141522/). Todavía, muchos misterios siguen

inexplicados, pero, yo creo, la información esencial queda clara: No somos

conscientes de todo lo que entra a nuestros ojos como rayes de luz y lo que sí

percibimos, sufre modificación durante su trayectoria hacia nuestra consciencia.

¿Deberíamos,

pues, cuestionarnos más sobre que realmente vemos? ¿Y que hay dentro de

nosotros, cual emoción, cual experiencia, que podría cambiar lo que percibimos,

cambiar la imagen que tenemos positiva- o negativamente?

Aquí hay otro artículo interesante sobre las "limitaciones de la razón" hablando sobre estudios recientes y la influencia de emociones en lo que pensamos y decidimos y como incluso nos convencemos a nosotros mismos de una realidad alterada: https://elpais.com/elpais/2018/01/26/ciencia/1516965692_948158.html.

Aquí hay otro artículo interesante sobre las "limitaciones de la razón" hablando sobre estudios recientes y la influencia de emociones en lo que pensamos y decidimos y como incluso nos convencemos a nosotros mismos de una realidad alterada: https://elpais.com/elpais/2018/01/26/ciencia/1516965692_948158.html.

Kommentare

Kommentar veröffentlichen